Getting older might be inevitable, but do you know how well you’re ageing? Of course, we can all look in the mirror, but what about under the bonnet where it really counts? Unfortunately, most of us don’t have a clue how well our bodies are holding up until something goes wrong and we’re faced with an unwelcome diagnosis. But now cutting-edge developments in the science of ageing are offering new ways to track the ageing process and turn back the clock.

“The idea is that deterioration is not just a result of chronological time,” says Dr Morgan Levine, an assistant professor of pathology, head of ageing in living systems at Yale University, and author of True Age. “Your age is not what’s driving that, it’s really these biological changes that our bodies undergo,” she says.

“So if you can prevent those or slow them, or, as some people believe, reverse them, then we can live longer in good health. I’m not saying they’re going to live to 150 years, but the goal is to keep people healthier the majority of the time that they’re alive.”

Research shows that only 10 to 30 per cent of our lifespan is determined by genetics, the rest is down to our daily choices. Unfortunately, most of us are in denial and in no hurry to change our habits, but what if we could see exactly how our choices were affecting the ageing process and also if any changes that we make are actually working?

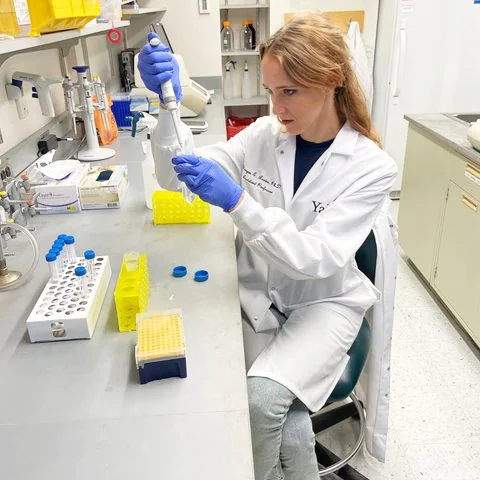

Hopefully, it will soon be easier, thanks to a new test like the one developed by Levine at her Yale laboratory. This is as simple as sending off a tube of your saliva to a lab, where they will analyse your “epigenetic code” to give a reading of your biological age.

Our epigenetic code is a set of instructions buried within our DNA, that modifies how our DNA functions. “I refer to it as the ‘operating system’ of the cell,” says Levine. But how does the test actually work? According to Levine it is based on something called DNA methylation. These are chemical tags that attach to our DNA molecules – they don’t affect the DNA sequence, but they can turn on genes that lead to good health or turn off genes that lead to bad health.

“There are billions of these in your genome,” explains Levine. “What we do is look at a few 100,000 to a million. And the thing is that cells have a very specific pattern of these tags. But with ageing, that pattern gets messed up. So we can look at someone’s pattern and say, ‘Oh, you have a pattern that’s similar to someone who’s 60 years old.’”

The test is just one of the many recent advances in anti-ageing medicine that Levine puts down to leap forwards in technology and our subsequent ability to measure millions of variables “even within a single cell”. Her test is already on sale in the US through Elysium Health at $299, and while Elysium doesn’t ship to the UK, other tests using DNA methylation, such as TruDiagnostic, do.

The TruDiagnostic test costs an eye-watering $499 (around £400). Levine hopes these kinds of tests will eventually be available for as little as $10 (she does not profit from sales herself). Fortunately, for those of us who don’t have a spare few hundred quid to splurge on a health test, a number of companies have created biological age calculators using Dr Levine’s research, which anyone can use at no cost, by inputting nine different blood test results, including red and white blood cell counts (CBC) and other substances that indicate the health of our organs.

Many of us will already have these in our NHS app, as they are often done as part of the NHS Midlife Health Check (though the NHS does not include C-reactive protein – CRP). “You can still get a good result just put in an average for CRP,” advises Levine.

The reason these algorithms give a clearer picture of our health is that they can sound the alarm well before any problems develop and also take account of how our systems interact within our body. Moreover, in contrast to the two or three test results we might get from a standard health check, the saliva test takes in millions of variables “to give a much more in-depth view”.

Ultimately, Levine is most interested in improving our “healthspan” – the number of years that we can expect to live disease-free. “Ageing research or longevity research often gets misconstrued with this idea that we are wanting to live hundreds of years,” she says.

“But at least for most of us in the field, the goal is how can we maintain the health and functioning that we associate with middle age or younger age for as long as possible and really delay or put off this deterioration that we usually associate with growing older,” she adds.

At 37, Levine is a good walking advertisement for her book’s lifestyle recommendations. Her current biological, or “true age”, is 34. “I was happy it was in the right direction,” she says. “It’s not as low as I would want, but I’m not actively doing that much to try and reduce it.” Not that she’s any slouch. She has been a pescatarian for 20 years, avoiding meat completely, runs to keep fit and fasts three times a year (see ‘How to turn back the clock’, below). In reality, her healthy lifestyle is likely to pay off more in years to come. “Younger people are pretty close to their chronological age, they’re really tight, there’s not a lot of variability, but the variability increases over time,” she explains.

Levine puts her passionate interest in ageing down to growing up with an older father, who was 54 when she was born, and a mother who was a professor working with older adults. “No one believed my father was my father,” she says. “He had amazing health for the most part, but I was still concerned if he’d be alive to see me get married, or meet his grandchildren.”

Much to her relief he was there for all of those things, as well as seeing her land her dream job at Yale University School of Medicine and she has him to thank for motivating her to dedicate her life to the science of ageing.

If we follow her advice and the research keeps advancing, how long might we live in future? “Right now, there’s an upper limit of 120 years, but there are definitely people who think we will live a lot longer,” she says.

“I’m perhaps a bit more pessimistic about lifespan. I’d be very happy if you could just keep really healthy for 100 years, especially as so many people get chronic diseases in their 50s. For most of us in the field, the goal is how can we maintain the health and functioning that we associate with middle age or younger age for as long as possible and really delay the deterioration that we usually associate with growing older.”

How to turn back the clock

1. Switch to a plant-based diet 75 per cent of the time

Protein has an ageing effect due to the impact IGF-1, a chemical involved in growth, has on the body. In a study of 3,000 Americans, at the University of Sydney, Levine and Dr Valter Longo, found that a high protein diet, with 20 per cent of calorie intake from protein, was associated with a 74 per cent increased risk of dying early compared to those in the low protein group of less than 10 per cent.

However, these differences disappeared when the protein was chiefly from vegetarian sources and those over 65 should be wary of cutting down too much. “It is a little bit nuanced,” says Levine. “Protein is not a problem for people who are young or middle-aged, because their bodies are still naturally generating enough growth hormone. But as people grow older, this is a time where I would say eating a little more protein, whether that’s healthy animal products or vegetarian forms might be beneficial, especially for people who might be losing too much muscle mass.”

2. Fast three times a year

Research by Levine, in collaboration with Longo, found that three cycles of fasting, eating only 4,500 calories over five days, reduced biological age, with subjects appearing 2.5 years younger. Fasted subjects also showed “more youthful immune profiles” following multiple cycles of fasting.

“It’s what we call a ‘hormetic’ effect, where it’s this mild stressor, and your body responds to that and improves,” says Levine. “Like exercise, fasting seems to prime the body for repair and maintenance.”

When the scientists looked at the potential long-term impact of fast mimicking diets (FMD) the data suggests that 20 years of FMD could buy individuals an extra five years of life expectancy, as well as reducing heart disease risk by 50 per cent, cancer risk by 30 per cent and diabetes by 75 per cent.

FMD is typically done once a month or a few times a year. In FMD each cycle consists of 4,500 calories, the first day is 1,000 calories; day 2 is reduced to 700 calories.

Focus on vegetable soups and bean soups and cut out meat and reduce your protein intake to 10 per cent. Other fasting methods like time-restricted eating also work to reduce biological age.

3. Do HIIT, high-intensity interval training

The short, sharp shocks of HIIT training are best for turning back the clock, says Levine. A 2017 study at the Mayo Clinic showed that three months of HIIT training was enough to substantially improve fitness and insulin sensitivity. “You do five or seven minutes, push, and then you get one or two minutes recovery,” says Levine.

The key is to go all out, aiming for 90 per cent effort. Again, it comes down to “hormesis”, where the body undergoes a shock, then adapts and improves. “Muscle fibres grow back thicker and denser, mitochondria becomes more efficient at generating usable energy, and processes like inflammation are turned down,” explains Levine. Exercise also stimulates GPLD1, a protein-coding gene that improves cognitive performance.

4. Good quality sleep

Research scientists at Boston and Harvard University used MRI scans to show that cerebral fluid (CSF) washes over our brain tissue in waves at night washing out dead cells. Scientists think this might have implications for Alzheimer’s, which is associated with the build-up of “amyloid beta plaques”.

Restless sleep might be due to the natural decline of NAD (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide), a protein that protects against oxidative stress and helps brain cells age well and also appears to be crucial to our circadian clock.

The best ways to increase NAD appears to be through fasting and exercise, though supplements are also available. Research shows the sleep sweet spot is around seven hours on average. Less than five hours reduces lifespan, as does more than eight, with 10 being the highest risk.