It was the year I got my first job, the year I broke up with my boyfriend, the year I flew to Barbados and met Imran Khan on a beach, but of all the crazy life-changing moments, none had more impact than the night I first experienced acid house, age 22, in the summer of 1988. I’d arrived at Heaven nightclub, underneath the Charing Cross railway arches, on a hot Sunday afternoon to find my friends had already gone in – you didn’t risk hanging back and missing your chance – so I joined the queue of kids dressed in the acid house uniform of Day-Glo dungarees and smiley T-shirts. I must have had the heads up on the attire as I was wearing baggy yellow surf shorts I’d just bought in San Diego, a far cry from the carefully curated layers of black that usually passed as a clubbing outfit, but other than that I had no idea what to expect.

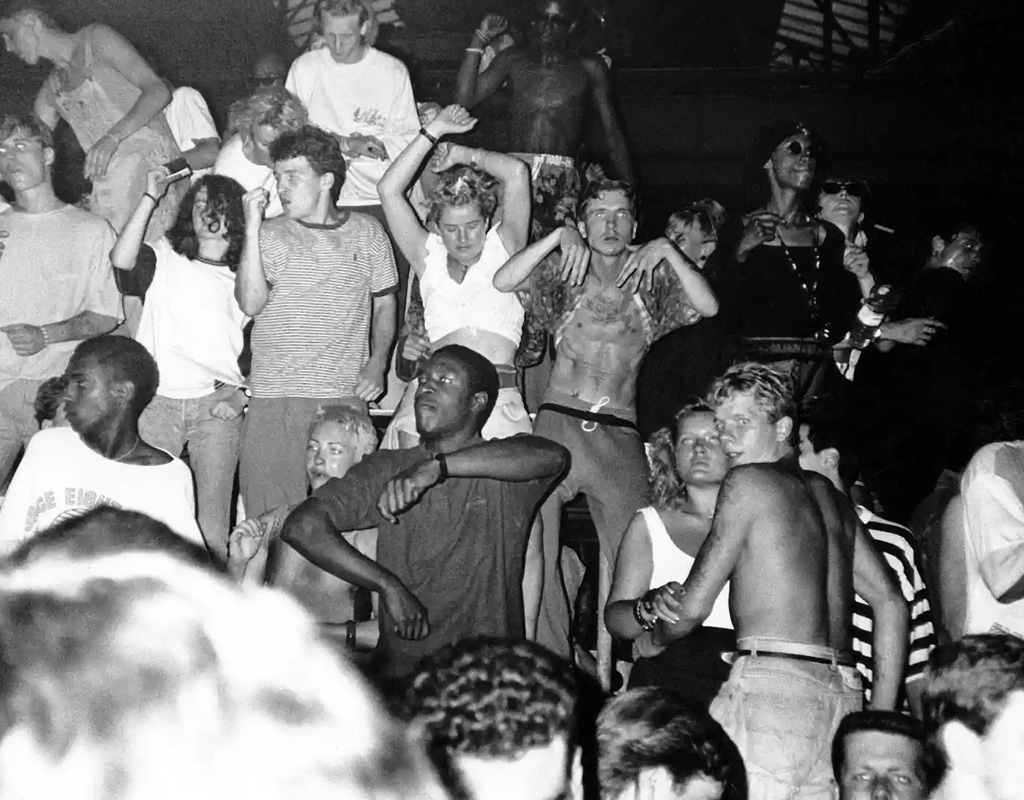

The minute I was through the door I was swept into a cavernous room of flashing lasers, dry ice and sweating bodies. After the self-consciously cool West End club scene I’d dipped into in the mid-80s, the club night Spectrum was a revelation. From the moment you stepped on to the dance floor everybody loved you, and everyone was smiling and swigging out of each other’s water bottles. Girls crowded around the mirrors in the bathroom telling each other they were beautiful. A girl in a swimsuit tipped buckets of water over her sweat-drenched body. I’d never seen anything like it. All inhibitions and barriers seemed to have dissolved in a heady mix of youth, summertime, the magical new music and, no doubt, a new empathy-inducing drug, called ecstasy, that many people had begun taking.

It’s 30 years ago this summer that acid house exploded in the UK, triggering what’s now called the second summer of love and the biggest youth revolution since the 1960s. As a Mexican wave of parties swept through London in a rush of joy and unity, a new world emerged from the swirl of dry ice and pulsing beats, one that was to shape our culture and outlook for the next generation.

As Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech echoed out over the dancefloor, the lasers cut in and a sea of hands reached into the air towards the DJ booth, I experienced something like a religious conversion. “This,” I thought, “is what I was born for.” Spectrum became my regular Monday-night haunt – that original party had been a monthly all-dayer – along with Future on a Thursday, both club nights started by the now legendary DJ and producer Paul Oakenfold. That first time I stayed all night and emerged squinting into the daylight, I went straight to my job at a fitness magazine with my ears still ringing, sure that I’d discovered this incredible secret.

From that moment on, I was out every night in an underground playground of warehouse parties, sweaty basements, abandoned shops and derelict railway arches. Club nights popped up and disappeared again like shooting stars and there was always the possibility that the police would turn up and pull the plug or the sound system would cut out and then we’d tumble out into the cold night air and head back to someone’s flat.

I don’t know how we heard about what was going on next. This was long before the internet and social media. It was as if there was a tribal drum echo on the street and soon I’d find myself in an abandoned coach station or sweaty basement in Camden locking eyes through the dry ice with a dancer from Cats, or a saucer-eyed plumber from Bromley. All barriers melted away. I met football hooligans who’d happily hug blokes from the other team as they “got on one” on the dance floor.

Rave culture had ushered in a new era of weekday partying and my first priority was dancing: Spectrum, Shoom, The Trip, Future, the exception to the rule was Westworld’s Enter the Dragon, at the Park in Kensington, on Friday night, which offered a rare glimpse of glamour, with its tiered glass dancefloors, where models and Chelsea girls rubbed shoulders with Portobello market traders.

Despite my busy school-night schedule, holding down a job hadn’t proved too difficult until my brother invited me to Ibiza where, after a weekend spent dancing on top of a speaker at Ku, under the stars at Amnesia and watching the sun rise on the terrace at Space, I called my boss on Monday morning to tell her I wouldn’t be coming back to the office, at least not that week. Two months later, I jacked it in to go to Goa where the party continued on the beach, dancing to electronic music surrounded by hippies who’d been there since the 60s.

By the following summer, the genie was out of the bottle and the acid house scene had taken off in earnest with massive raves around the M25. My friend Tash, who I’d met on that first night at Spectrum, was working behind the scenes with a professional gambler called Tony Colston-Hayter on his Sunrise raves. It was her voice you’d hear when you called the BT phone line for directions to a secret rave location. There were parties in fields, at Didcot Railway Centre, in stately homes and, one memorable night, at a mansion in St John’s Wood, with a baby oil dance floor and a Rolls Royce in the drive. After the party, we’d carry on back at someone’s place. One day, after dancing all night in a field near Brighton, I led a convoy of cars to my dad’s house in Kent, where Norman Jay played in the garden.

But the energy had begun to change. The tabloids had whipped up a moral panic in middle England and police vans would be waiting for us in fields as we drew up to the gates. The carefree spirit had gone out of it, at least it had for me. I got a job and started seeking out smaller, more grown-up clubs, like Graham Ball’s soulful Quiet Storm and Sara Blonstein’s glamorous Pussy Posse parties, which were incredibly creative, with their kissing booths, four-poster beds and “dating agencies”.

You could say the acid house movement was pure hedonism, but bigger cultural changes came of it, as people began breaking away from the “greed is good” 1980s. That summer certainly had a huge impact on me. The bleak depression and feelings of isolation triggered during the last year of university, after a painful break-up, had lifted in the swirl of dry ice and smiling faces and, for the first time in my life, I’d truly felt part of something. Even now, 30 years on, I’m still drawn to that kind of optimistic energy and moments of connection and, like many of the friends I met that summer, it’s hard to stop me jumping up and down to an uplifting Balearic beat.

Danny Rampling: the catalyst

DJ, 56, founder of Shoom, the club credited with spearheading the acid house scene in London

The inspiration for Shoom came from a trip to Ibiza to celebrate Paul Oakenfold’s birthday in August 1987. We went to this open-air, after-hours club called Amnesia where DJ Alfredo was playing and that was a pivotal experience. It was a combination of the spirit of Ibiza, the spirit of the people and this revolutionary new music, house and techno. We returned to London and sprinkled some of that Ibiza magic into the clubs we created. When I created Shoom in a basement gym in Southwark, it was a complete breath of fresh air. It was small and intimate and it attracted a group of like-minded people of all races, colours and sexual preferences, a mixture of art students, street kids and fashion people. It only held 300 people, but within a few months there were thousands waiting to get in.

By 1990, the rave scene had deteriorated, but that first couple of years people felt like they were really part of a tribe. Acid house was completely inclusive, everyone was welcome and the attitude was infectious. I’m just very grateful to have pioneered that part of the scene.

Danny Rampling is releasing Space Girl with vocals from Irvine Welsh this summer and hosting Summer of Acid at Club Paradiso in Amsterdam on 24 August. He is playing with DJ Alfredo at the Prince of Wales, Brixton, 7 July

Terry Farley: the curator

DJ, 59, co-founded the Boy’s Own fanzine, described as the “village newspaper of acid house”. He also hosted Boy’s Own parties with Andy Weatherall, Cymon Eccles, Steve Mayes and Steve Hall

It was a brilliant summer, a beautiful summer. It was almost as if every week there was a standout moment. Everyone was so excited and into it. It was all about trying to do something where you’d go: “Wow, that was amazing.” All the DJs were trying to find records that would make perfect sense on E. So you had people looking for rare records from the 70s, 80s and even back to the 60s.

One of the best moments for me was the first party we put on in late spring 1988. We wanted to recreate that outdoor Ibiza experience and Cymon [Eccles] found this guy with a big house with a recording studio and a barn in Guildford. At one point in the morning Boy George was there singing with the bloke who owned the house, strumming away on a guitar and the police turned up. They looked around at the mayhem going on, with 300 people in a state of euphoria, and just asked what time did we think we’d be going home. They were very nice and polite. A week later it all exploded and police were kicking in doors and arresting people. So there was that little golden moment when everything was perfect and there was no one there to spoil anything.

I don’t think the acid-house culture ever really finished. Without it you would never have got garage and without garage you would never have got grime, so basically the biggest music in the world now owes a debt to acid house.

Boy’s Own are doing a stage at the Farr festival, Bygrave Woods, Hertfordshire, 7 July

Tintin Chambers: the outlaw

Club organiser, 48, co-founded Energy, putting on raves for up to 25,000 people, with Jeremy Taylor

By the time we started doing the big outdoor raves in mid-1989, the police Pay Party Unit numbered over 50 officers and were following everything we promoters did. They even had helicopters circling the M25 on a Saturday looking for us setting up. Pretty much every party we did ended up causing quite a bit of disruption. Once we even closed down Heathrow when we set up behind Heston services. The police got wind of it and blocked all the approaching roads. People were parking on the M4 hard shoulder and scrambling up the banks to make a run for the fence, while police dogs were being set on them. It was pretty chaotic. In the end there were 10,000 people inside the party and 1,000 police outside. After that party, Jeremy and I were arrested by plain clothes police dressed like ravers in dungarees and driving a 2CV, with a smiley face sticker in the window. You really could not make it up.

The Mirror labelled me an evil acid house baron and accused me of corrupting the nation’s youth, but I didn’t take much notice. We didn’t think what we were doing was so bad – a bit naughty maybe but not evil – we weren’t gangsters, we weren’t hurting anybody, and it felt as though people were behind us. Faced with a road block today, I think most people would probably turn around, wouldn’t they? What made us so determined? We were having the most unbelievable time, a unique experience, shared with hundreds and then thousands of people. Really nothing like this had happened since the 1960s.

Tintin Chambers still works in the music business

Joe Rush: the artist

Club organiser, 57, founder of the travelling art collective the Mutoid Waste Company

We were already doing parties in old warehouses around London when acid house hit. They were one-night festivals, with a heavy emphasis on the sculptural stuff, with cars hanging up, like a big adventure playground. It was this mad Disney World with no rules that was a Mutoid Waste party. Then Sex Two, who I’d say were the first acid house sound system in England, turned up and took over the old canteen block behind us in Battlebridge Road, King’s Cross. It was amazing: 5,000 people squashed in, raving away around a single lightbulb to Can You Feel It by Mr Fingers, an early Chicago house music classic. I thought: “Fucking hell, this is really something new. This is mad.” It blew everything open. Suddenly you’d have the City boys in their souped-up cars, the crusties in their old bread vans and everyone was on the same buzz. There was this weird synchronisation where all the different cultures and even the football culture came into it. We’re English and we’re very tribal – suddenly it freed us up from all that. Suddenly we were all on the same buzz, rushing away and feeling good and full of love. It was a fantastic thing, but in the end there were too many criminal gangs fighting over the action and that spoilt it a bit.

People got too out of it on E, with brains like overcooked vegetables, and I think we paid for that. You can’t get enlightenment in pill form. You can get insights and moments of lucidity, but you’re not going to get it by partying every weekend, which is the same conclusion Timothy Leary came to with acid at the end of the 1960s.

The Mutoid Waste Company has an exhibition at the Bruton Art Factory in Somerset, 30 June-31 July

Natasha Monro: the voice

Club organiser, 47, worked on Sunrise raves giving out directions to the secret locations of the M25 parties

I was 17 at the time, so I didn’t have a job, but I was selling tickets to parties and raves to fund going out, which is how I met Tony Colston-Hayter who put on Sunrise. It was my job to update the 0898 numbers that gave out the secret locations, which we did for all the raves, Energy, Back to the Future, Biology. It was my voice you heard if you were heading to the big raves that summer.

The location was always a closely guarded secret until the last minute, so that the police wouldn’t arrive and shut you down. I was probably the most hated person in England whenever anything was cancelled or redirected. A particular moment of pride was when the BBC did a story on the orbital/M25 scene and they played my voice, giving out directions on the news.

Occasionally I had to change the messages on location and that meant finding a phone box, though I must have had a mobile at one point because I remember climbing on top of a bus to get reception and telling people how to get past a police blockade on the way into an Energy party. There was usually a QC on site who’d give us legal advice and on that occasion the security led people through in big groups, peacefully, and there was nothing the police could do about it. It wasn’t illegal at that point. It was only when the media started demonising the scene that the police started arresting people.

If it hadn’t been for that summer of love, I wouldn’t have met the incredible group of people I’m still friends with today, or my husband the DJ James Monro who says he first clapped eyes on me when I was dancing on a podium at Sunrise, though neither of us can remember which one. Now James and I run a small charity in Brazil for troubled teens and one thing that helps us to understand them is my experiences as a teenager.

Nick Coleman: the designer

Nick Coleman, 56, co-founded the underground Sunday House Music club Solaris, with partners Roscoe and later Dave Manders.

I had a fashion brand at the time which was doing very well. I was dressing all the popstars and it was selling in 200 of the best designer fashion shops around the world. The look was quirky British tailoring, “Punk Couture”. It was a very smart dressed up look that reflected the club scene at the time. Then one evening in July 1988 I was taken to a club called Shoom and there was in my designer clothes, but there was a completely different look and music, it was unlike anything I’d ever heard or seen before. Everyone was really open and friendly and you could have amazing conversations with someone you’d just met. No one was drinking beer and at first I didn’t understand what was going on, but I soon found out. It’s no coincidence that Danny Rampling used the smiley face as the Shoom logo because everyone was smiling and losing themselves in this incredibly powerful music. Prior to that if you went to club you had to stand around looking cool, so this was an incredible change

It was just one of the moments when I suddenly realised: this is something big. It was the beginning of a new youth culture and it was very obvious to me straight away. The next week I was there in a t-shirt and white jeans and I had 50 new friends. I completely changed the look of my fashion brand overnight. My colour palette went from monochrome, black, white, and grey, to bright colours, loose shapes and eclectic prints. I quickly became submerged in the house music scene, with all these new friends hanging out at my house on a daily basis, which is when we decided to start Solaris. This was initially aimed at the real hardcore ravers who been out all Saturday night and wanted to carry on for the rest of the weekend. Initially it ran from 12-12 and became quite a cool place for music people to hang out, we had lots of famous house DJs, like Mike Pickering, Graeme Park, Andy Weatherall and Terry Farley playing and we put on bands like The Shaman and Adamski. One night Malcolm Mclaren came down to the club with Keith Allen which was a bit surreal.

On another night as we were packing up a tall black guy with dreadlocks gave me his demo tape and asked if I wouldn’t mind listening to it. He was looking for advice getting into the music business. We all piled into my car and I put on the tape. We were all saying: ‘This is incredible.’ We ended up hooking him up with Adamski and they formed a close friendship and went on to perform Killer for the first time in the club a few weeks later which later became Seal’s first hit. As a result of the house music scene I nearly got out of fashion altogether and into the music business. And I think that time had an impact on the way I think now, I’m much more open to new possibilities. I became interested in Buddhism and starting thinking about how the world could be a more peaceful, less violent place. It was certainly a quasi-spiritual awakening, when everyone realised it was much more fun to be open and friendly than it was to be negative. At the time wWe felt that we were part of something that was really going to change the world and it was a very optimistic time.

Nick now runs the wellbeing brand Calmia with his wife Lucy Wakefield.